19:00 Presentation: Santos Zunzunegui

20:00 Projection: VAMPIRESAS 1933 (Gold Diggers of 1933), Mervin LeRoy y Busby Berkeley, 1933

In his noteworthy documentary entitled A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese through American Movies (1995), this filmmaker from New York reminds us of the existence of three film genres that are genuinely original to the USA: the Western, Gangster cinema, and --of course-- the Musical, which eventually brought that well developed tradition from the theatres of Broadway to the big screen. And he points out straightaway that the latter of those three genres was the one that broke out most in that its initial blooming at the beginning of the 1930s coincided with the start of sound films and a deep economic depression which required an emotional "escape" in the form of stories that would help the public to aspire for social improvement. But, as is the case more often than it seems with American cinema, intense contact with real life has always been kept by means of a unique combination of reality and dreams -- and this will be seen shortly.

It is likewise not surprising that, as sound was introduced to film, the world of the musical show was to occupy a privileged position in terms of entertainment -- and there was no easier way to accomplish that than to include shows in films that had already been tested in the theatre. Thus, a plotline that had already been developed in theatre was naturally added to the cinema: pieces that dealt with the difficulties implied by putting on a musical show, making the miseries experienced by the unemployed actors and musicians an important part of a plot. Added to that --and in line with the tradition that, at that time, was becoming the norm-- was the fact that all films (regardless of their genre) had to draw support from a second storyline that was firmly anchored on a heterosexual love story (or several love stories, as is the case of Gold Diggers of 1933, in which these love stories are also used to bring together a series of inter-class ties). In fact, this norm was even etched in black and white in the scriptwriting manuals prepared by the large producers at the time.

The second major musical production by Warner (the leading producer in those years for this film genre) in the wake of the successful 42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon and Busby Berkeley), a film which also should have been directed by Mervin LeRoy (he wasn't able to do so because of other work for the studio that he had going at the time) and which brought together a number of names that, for the next five years, would shape the musical film genre at the time. Starting with the pair Harry Warren (songwriter) and Al Dubin (lyricist), followed by a plethora of actresses (noteworthy are Joan Blondell, Ginger Rogers, Dolores del Río, and --especially-- Ruby Keeler) and actors (Warren William, Warner Baxter, Dick Powell, and also James Cagney) capable of navigating stories that seemed to be aimed towards what would soon be known as screwball comedy with ease and without allowing their dancing and singing to suffer. Especially, the inclusion of one artist as the person in charge of design and staging for the musical numbers (legend has it that he had no specialised professional training but that he had been a smash on Broadway as a choreographer and businessman) – someone who had made it clear just a year earlier in a production by Samuel Goldwyn entitled The Kid from Spain, starring Eddie Cantor, that he had perfectly understood that musical numbers in the cinema had to always seek their own conceptual and visual route, no matter how much the stories they presented seemed to confine them to the theatrical stage. That person is William Berkeley Enos, known for posterity as Busby Berkeley.

As was the case of 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933 got its inspiration from a pre-existing piece that had debuted on Broadway during the 1919-20 season and which reached almost three hundred performances. What's more, the show (also entitled Gold Diggers) had two earlier film versions (and one of them was even silent). In both films, the story revolved around the launch of a musical show, the difficulties to find financing for that type of project, the adventures of a group of young people who aspired to be artists, their love affairs, and their work to make a name for themselves in the turbulent world of show business. Rehearsals and opening night served as a pretext to insert the musical numbers (in fact, these scenes open and close with a curtain rising and falling). These were musical numbers that could afford a great deal of autonomy in terms of the story they were included in and which allowed the choreographer's imagination to run wild (and this was certainly the case of Berkeley's imagination).

Gold Diggers of 1933 has a total of four musical numbers (there were originally five) that were completely conceived, organised, filmed, and edited by Berkeley: the film's opening number (a rehearsal for a show, which is interrupted by the indignant claims of the creditors) entitled “We’re in the Money” (starring Ginger Rogers) was performed with a group of female singers whose bodies are strategically "decked out" with dollars – it was intended to say goodbye to the bad times and the depression. That number is followed by “Pettin’ in the Park”, which features the stellar pair made up by Dick Powell and Ruby Keeler. In this number, Berkeley gives free rein to his voyeuristic delusions. Once again, Keeler and Powell star in “The Shadow Waltz,” which allows the thoughts that underlie the work of the filmmaker to be understood. In his own words: “one day in New York, in a theatre, I saw a young lady who was dancing with a violin and I told myself that one day I would do that with twelve girls or more. Another day, I saw four pianos on a stage and I thought that, at some time in my career, I would include twenty or thirty in one sequence.” Said and done: the magnificent dance of the neon violins in Gold Diggers of 1933 and the sequence with the white grand pianos in Gold Diggers of 1935 are perfect examples of that style of “quantitative” thinking: for Berkeley: “more is more.” But, alas, the best is yet to come. In fact, the number entitled “Forgotten Man” was not designed to close the film, as it ended up doing. It was Darryl F. Zanuck, one of the studio's main executives who made the (great) decision to make this number the film's apotheosis. In this sequence --inspired (as Berkeley tells us) by the World War I Veterans' Protest March that took place in Washington, D.C. in 1932-- the way that American society treated its young solders that had been sent to the far-off European war theatre, their return home, the hardships of the Great Depression, and the wounds inflicted by economic disaster upon a society that had not yet recovered are all plainly mentioned. “Are we in the Money?” Berkeley seems to be wondering, echoing the opening scene. It does not seem unreasonable to think that this number may have been one of the main causes cited for the film's being chosen in 2003 by the Library of Congress National Film Registry to be preserved because of its cultural, historic, and aesthetic significance.

There is another element that makes the film interesting. The fact that it is one of the last films before the entry into force of the Motion Picture Production Code (effective without restrictions as of 1934), more commonly known as “Hays Code,” a guide on self-censorship by the studios to avoid the intervention of the authorities from the different States (each with their own laws) in defence of "good customs" by “moderating,” motu propio, the most controversial aspects of the films they produced. In fact, there is documentation speaking of three versions of the film depending upon its target area: New York, the South of the country, and the United Kingdom. In the three versions, alternative takes of numbers like “Pettin’ in the Park” and “We’re in the Money” were used depending upon the destination.

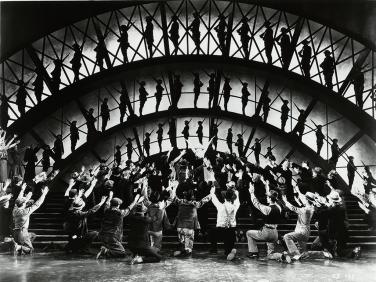

None of this would suffice if it weren't for the fact that the four musical numbers mentioned led the style (it is nothing less than this) that Berkeley had perfected between The Kid from Spain and 42nd Streetto paroxysm (but, although hard to believe, things could get better in later works). Not in vain did the trailer for Gold Diggers of 1933 claim that the new film was a step forward compared with 42nd Street. All of the characteristics of Berkeley's art can be clearly identified in the piece we have at hand. An art that achieves a show (in the words of Jean-Louis Comolli) and makes the kaleidoscope its central visual figure. Like the images produced by a kaleidoscope, the images of Berkeley move between division and re-composition; the infinite combination of fragments that are, in the end, reduced to a series of symmetrical compositions filmed from the most surprising of angles in a fascinating interplay of analysis and synthesis. Angles amongst which what the industry came to call a "Berkeley shot" stands out -- a view from above of forms in which the tangible dissolves into a visual abstraction that is a mere representation of the original forms (but with much more glamour, beauty, and —of course— humour). This shot was all the rage in the misnamed “pure cinema” of the first avant-garde filmmakers.

Berkeley, who was proud of never having shot a second take of any of his scenes, no matter how complex they were (everything had to be —and was— perfectly designed and under control before starting filming), recorded all of his pieces with a single camera, not accepting the offers of the studio from the very beginning to multiply the points of view to make editing easier later on.

In the end, Berkeley's work takes the notion of show to the extreme, with his work being a true show of shows. One could say that his sequences, inserted in the conventional narrative of the comedies in which they appeared, are as important as sleep in terms of our daily life. That is why all of Berkeley's work has a meta-cinematographic dimension. We could fully agree with the comment by Comolli that we are before a “true explorer of dreams and of cinematographic language”, a comment which claimed that Busby Berkeley understood, as few filmmakers ever have, that the mechanics of dreams and the cinema are intimately intertwined; and it is exactly that fact which (again, as Comolli says) makes the “arbitrary” —that utter freedom that comes from visual splendour— “end up becoming the truth.”

Santos Zunzunegui

19:00 Presentation: Santos Zunzunegui

20:00 Projection: Gold Diggers of 1933 (Berkeley,1933)