19:00 Presentation: Santos Zunzunegui

20:00 Screening: Two-Lane Blacktop, Monte Hellman, EUA, 1971, 101'

TWO-LANE BLACKTOP, MONTE HELLMAN, 1971

The 1960s was one of the most critical periods for the huge companies that, up until then, had ruled the destiny of North American and global cinema. Spectator numbers in the USA – which had peaked at 110 million annually in 1930 – were constantly diminishing and had plummeted to just 40 million by the late 1950s after a short-lived surge during the years immediately after the end of the Second World War. At that time, box office takings had reached a historical high and spectator numbers had temporarily recovered to an encouraging 100 million per year. From then on, however, all financial indicators would point once again to a decline. There were multiple, complex causes. The first wake-up call came in 1948 when the US Supreme Court passed an anti-monopolistic ruling, forcing the Hollywood majors to give up their vertical business model that had enabled them to control the entire cinematic process from studio production through to screening in movie theatres.

However, the most important transformations came in the form of sociological changes in North American society, particularly the growing move of large population hubs to new suburban residential areas. Old movie theatres, now in increasingly deserted urban centres, were bereft of their potential audience, and the drive-ins in the suburbs weren't profitable enough to replace them. To make matters worse, the emergence of a new form of entertainment – the television – gave people access to audiovisual material that was free of charge and controllable from the comfort of their own home. The TV would become a serious opponent for those who had been shaping our collective imagination for generations throughout the 20th century. By the late-1950s, 90% of North American homes had the latest in-home entertainment.

Hollywood explored all possible options for continuing to provide attractive forms of entertainment that would somehow reverse a seemingly irreversible trend. The old ‘double bill’ trick, where the ticket price for a major feature film included the screening of a B movie, would be followed by the introduction of mainstream colour cinema, new screen formats designed to compete with the ‘postage stamp’ format of domestic television sets (CinemaScope, Cinerama, Todd[A1] -AO), 3D cinema, the trial of what would later be known as blockbusters (between 1960 and 1965 Bronston would test this format in Spain) and even a limited yet decisive move towards increasingly adult movies which were less affected by censorship.

None of this, however, was strong enough to win back an audience that was increasingly reluctant to return to dark movie theatres. Something was changing forever, and there was irrefutable data to confirm it: whereas in 1930 the percentage of the American population that went to the cinema on a weekly basis was a record 65%, by 1932 it had fallen to 42%. It rose to 60% during the Second World War before nosediving between 1949 and 1959 to a depressing 25%. By 1964, the figure had plunged to 10% and remained below this for the rest of the decade.

On top of this, other profound transformations were having a profound impact on a youth that didn’t identify with many of the values that their elders had lived by for decades. Roughly speaking, the earthquake that was shaking American society was founded on a significant liberalisation of traditions that particularly affected the youngest segments of the population (the children of the Baby Boom) and intellectuals, the spread of various social movements including the rise of the fight for more civil rights for minorities (particularly during the first half of the 1960s), and the emergence of a student movement that stepped off campus to demonstrate their opposition to the war that had the USA bogged down in Vietnam (it would continue until peace was reached in 1973) and their involvement in racial conflicts that would lead to radical offshoots such as the Black Panther and Weathermen movements. Also in play was the popularisation of a drug culture supported by the diverse hippie counterculture – an anti-consumption, libertarian and pacifist movement that challenges the establishment, drinks from different sources (an idea from Buddhism, the pre-ecologist thought of H. D. Thoreau, the ideas of Mahatma Gandhi[A2] ) and is not afraid of taking part in social protests, all while searching for altered states of consciousness (via the use of psychedelic substances) that facilitate an inner journey that goes hand in hand with the vagabond exterior which is so symbolic of hippy identity. The dream would reach both a climax and a crisis point in August 1969, during a month which saw both the Woodstock festival and the Manson family murders.

To survive amid this complex state of affairs, the big cinema companies had to diversify their income streams and look for financial partners. The large studios of the time were typically – unstoppably even – absorbed by huge financial conglomerates in which film was not necessarily the most important global business stream. MCA (Music Corporation of America) was acquired by Universal in 1963, GULF + WESTERN took control of Paramount in 1966, Seven Arts absorbed Warner in 1967, and a new conglomerate called Warner Comm. Co was formed just two years later from the merger of Warner/Seven Arts with Kinney-National S. (it had real estate businesses, manufactured recording devices and produced advertising spots).[1]

This period marked the last hurrah of several names that had taken American cinema to its artistic apogee, thus exacerbating the situation further. Raoul Walsh made his last film in 1964 (A Distant Trumpet), John Ford completed his magnum opus in 1966 (7 Women), Chaplin would make his last film in 1967 (A Countess from Hong Kong), Fritz Lang had filmed his final movies far from Hollywood, in India and Germany (Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb, both 1959; The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, 1960), and Howard Hawks would round off his career with a return to some of his favourite genres (Hatari!, 1962; Man's Favorite Sport?, 1964; Red Line 7000, 1965; El Dorado, 1967; Rio Lobo, 1970[A3] ). What’s more, film makers of the next generation who tried to make it on their own (among them Otto Preminger and Vincente Minnelli) would show without question that certain types of artists relied on the Taylorist discipline of the old studio system. Only Alfred Hitchcock stretched his careed into the mid-1970s (Topaz, 1969; Frenzy, 1972; Family Plot, 1976), albeit with films that lacked the vigour of his best works.

In short, despite the emergence of one or other great talents (we’ll mention only Jerry Lewis), everything seemed to herald the Götterdammerung of the old Hollywood, amid the hope that the phoenix would rise once more from the ashes.

*

Towards the end of the decade, three very different movies showed Hollywood’s old guard that, after thirty years at the helm, it would have to make changes to survive. Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, Warner Bros.) and The Graduate (Mike Nichols, United Artists), both from 1967, and Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, distributed by Columbia) in 1969, made the old executives realise that there were other channels to explore in the name of recovering the lost spirit of American cinema and creating a ‘new Hollywood’. The recycling of classic genres to match the new times, the exploration of youth sexuality, and a focus on the new counterculture that was transforming North American society all came together with the fact that the big studios were already well ahead in diversifying their interests. In fact, film was one of the least lucrative businesses for many such studios compared with the youth music industry and TV. The books had to be rebalanced in the various departments of the large financial conglomerates that had acquired film studios.

This was certainly the case at Universal. After rival companies had identified a potential goldmine, managers Jules Stein and Lew Wasserman decided to throw everything they had to get young audiences back into movie theatres. The key decision was to put a 37-year-old Ned Tanen from the music department of MCA in charge of a production unit for feature film productions that would cost no more than a million dollars to make (including Two-Lane Blacktop, which cost around $875,000) and would be directed by new emerging film makers. The latter would also be given control over the final cut – unthinkable in the decades prior. Tanen immediately set a production plan in motion to follow the success of Hopper’s movie with three feature films based on the same ingredients. Two of the films involved the ‘rising stars’ of Easy Rider: Peter Fonda, who in 1971 would bring The Hired Hand to the big screen, and Dennis Hopper, who would film one of the biggest cinematic disasters of the time in Peru called The Last Movie (1971), amid a wild and megalomaniacal atmosphere of drugs and sex.

The third project also hoped to ride on the success of Easy Rider with the open road, speed, and freer personal and sexual relationships. One of the first drafts to land on Tanen's desk was from another producer in his thirties called Michael S. Laughlin. He had recently returned to the USA after several years in the UK, where he had produced two films with varying degrees of success. He soon set some budding writers to work on a couple of scripts: one by Floyd Mutrux, called The Christian Licorice Store (it would be brought to the screen by the writer himself), and the other by Will Corry, who already had some experience as an actor and writer for TV series. Corry’s script, called Two-Lane Blacktop, told the story of two young hot rod[2] fanatics, one of them black, racing at the wheel of their modified 1955 Chevrolet two-door against a group of rich kids driving a new as-standard 1970 Pontiac GTO. The prize for the winner of this race across the USA would be their opponent’s car. Everything pointed to the movie being a four-wheeled Easy Rider.

It’s no surprise that Laughlin’s choice of director was a film maker mentored by Roger Corman, known as the ‘Pope of Pop Cinema’ since the 1950s. In fact, several major names from the New Hollywood were trained under Corman. Laughlin chose Monte Hellman. Tired of fruitlessly investing in his own theatre company, and with no experience behind a camera (though he did have editing knowledge), Hellman had made two negligible ‘Corman factory’ films a few years before (a horror movie, and a war film) which revealed that there was skill hiding behind his modesty. In the mid-1960s he made two unique and simple westerns starring Jack Nicholson (The Shooting, 1966; Ride in the Whirlwind, 1967). These had only limited TV screening the USA but enjoyed notable critical acclaim in France. It was the perfect combination to convince both Laughlin (Cinema Center Films) and Tanen (Universal): cultural prestige from across the Atlantic, just as ‘new waves’ were breaking out across the world and subverting all the rules of cinema; and a knack for navigating the muddy waters of small generic productions.

Hellman read the scripts and immediately took an interest in the project, but he had one condition: it would be rewritten by a young writer called Rudy Wurlitzer[A4] . In a presentation on the publication of the script, made in 2007 by Criterion for their DVD release of Two-Lane Blacktop, Hellman describes how the film was eventually written: ‘Rudy read five pages, and said, “I can't read this”, and I said, “well, you don't have to. The basic idea is a cross-country race between two cars”, and so he wrote a completely new script that had pretty much no relationship to the original other than the Chevy 55, the Driver, the Mechanic, and the Girl, which were heavily altered. And that’s all, as far as this topic is concerned. Rudy invented GTO and the Pontiac he drives. The other characters were also invented by him.’

The story can be summed up thus: Two young guys (The Driver, The Mechanic) who live for illegal car races at the wheel of their hot rod (their 1955 Chevrolet two-door) pick up a young hitchhiker along the way (The Girl). They cross paths with an older driver (GTO) in an as-standard 1970 Pontiac GTO. They challenge him: the first to get to Washington D.C. will surrender their car to the other. The characters (along with Hellman and his team, who made the selfsame journey while filming on location) cross much of the USA in what is a dystopian version of the mythical original journey from east to west, only the other way round. The film ends before they reach their planned destination.[3] Si siempre puede sostenerse que un filme contiene en sus imágenes un documental de su propio rodaje, en el caso que nos ocupa es muy evidente que los fotogramas de Carretera asfaltada en dos direcciones It could be said that a film’s images are a documentary of its own shoot. In this case, the frames in Two-Lane Blacktop owe much of their power to how they ‘record’ the journey undertaken by the team during the shoot.

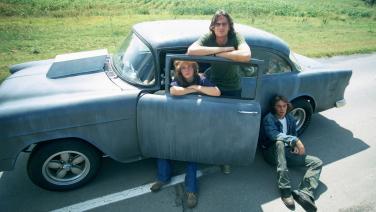

From the outset, Hellman ruled out giving the starring roles to well-known actors. After rejecting Bruce Dern for the role of The Driver, he chose a 23-year-old singer – a young James Taylor, whose music career would take off as the film was being shot. Taylor, who would never again get in front of a camera, demonstrates one of the most secret relationships in a film to which he brings a visible blend of curiosity and reticence. As Richard Linklater says, he seems like he’s escaped from a Robert Bresson film, and it’s one of the few cases in which, beyond his own work, we can talk properly about the notion of the model coined by the French master. After much wrangling, the role of The Mechanic would be played by another very young musician with no film experience to speak of: Dennis Wilson, drummer and singer in a pop group then at their peak. This is no understatement, given the group we’re talking about is the Beach Boys[4]. For Universal, these choices fit like a glove with their goal of fusing film, youth and music. In addition, an unknown aspiring model from New York called Laurie Bird, who was underage at the start of the shoot and had a relationship with the director, would play The Girl. It reminds us of Ingrid Bergman in the grasp of Rossellini, and we can’t know for sure whether her ‘performance’ depicts a fictional character or shows us the real questions and inconsistencies of an immature young girl caught up in an inquisitive objective (it is undoubtedly both things at once). As we’ve already alluded to, much of the film’s strength lies in this germinal confusion, and nothing demonstrates it better than scene 59 in Wurlitzer’s script, filmed in an old gas station on the outskirts of Tucumcari. In a shot lasting a minute and a half, we see The Driver and The Girl sitting on a wooden fence. Against the persistent background noise of the cicadas, The Driver tells a perplexed Girl a small parable about the life and habits of these strange animals.[5] The main cast was completed by an experienced professional by the name of Warren Oates. He had already worked with Hellman on one of his westerns and this time would play GTO, the opposing driver.

Hellman would make another two important choices. Gary Kurtz, who had assisted with Ride in the Whirlwind, would be executive producer,[6] and in an even more significant decision he would put the man who lit his two westerns in charge of cinematography: the Hungarian cameraman Gregory Sandor. Think about it. Since Two-Lane Blacktop was a studio film, Hellman needed a cinematographer who was a member of IATSE (the elitist International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees), to which Sandor had not been admitted. The credits list John Bailey as 'assistant camera’ (he provided trade union coverage to the shoot and was a key collaborator of Sandor's), and a ‘photographic advisor’ to recognise the real contribution of the Hungarian cinematographer. Sandor’s extraordinary work combines utmost simplicity with absolute precision and remarkable compositional elegance. On few occasions had the wide screen (the movie was filmed in 2:35 Techniscope, enabling each element in the frame to be in focus) so clearly been one of the decisive visual elements of a film.

Hellman insisted that the film be shot according to the scene order in the script, and that the actors have no knowledge of the scenes they would perform until the night before the shoot (to stop them from building a character). The cast and crew began a journey that would take them from Los Angeles to Maryville, North Carolina, passing through Needles (California), Flagstaff (Arizona), Santa Fe and Tucumcari (New Mexico), Boswell (Oklahoma), Little Rock (Arkansas) and Memphis (Tennessee), between August and October 1970. In parallel, Universal was beginning a publicity drive intended to turn the film into a success before it even existed. Big publications such as Rolling Stone and Esquire (which put Laurie Bird on the cover of one of its 1971 issues and discussed the ‘film of the year’) talked about the shoot.

The first cut ran to three and a half hours and stuck meticulously to the script. Though Laughlin and Hellman had been granted control over the precious final cut by Universal, the contract contained a clause preventing the film from going over two hours. Almost half the run time was cut from the final version, bringing it down to 105 minutes. Not only did the premiere in July 1971 not meet Tanen and Laughlin[A5] 's expectations, the film was a huge flop with the Universal executives who, in addition to dealing with the chaos created in Peru by the filming of Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie, failed to comprehend Hellman’s directorial style. To them, the fact that the film had no soundtrack, other than the diegetic music that we hear in various places or in GTO’s car, didn’t marry with the presence of two famous musicians, not to mention that the director shunned any desire to impress by closing his scenes with a gradual silence. On top of this, they would find the contribution of the ‘non-actors’ too idiosyncratic, and the ending beyond belief. Despite its successful screening in France and Japan to significant critical acclaim, its failure at the box office would ultimately seal its fate.

After that, the ‘window of opportunity’ created by a unique conjunction of circumstances closed, and the film disappeared into oblivion. It wouldn’t resurface until years later, by then a crucial piece of American cinema from the early 1970s. As part of Hellman’s film retrospective in 2000 at the South by Southwest festival in Austin (Texas), Richard Linklater described it as ‘the purest American road movie’. He also highlighted its links with Robert Frank's photography in The Americans, a masterful visual depiction of the real America.

*

Why is Two-Lane Blacktop so important? First is its symptomatic value. The film uses its choices to reflect the American counterculture of the time, present in the mythology of the cars, the hippy world, wandering with no clear destination and folk rock music. Furthermore, it makes a primordial reflection on said counterculture. That is, it doesn’t show us spectacular places and eccentric characters and drug culture (acid, cocaine) like pieces such as Easy Rider did, but in a very subtle, muffled if not silent way, focusses on the ‘backyard’ of North American society. There’s nothing fancy, and as Wurlitzer [A6] said, it refrains from bringing to the fore the political dimension of the depiction of a time and place. As he himself said, it’s as though the film were a western that made no reference to the Civil War.

While we're on the topic of westerns, we could reasonably assert that, in its own way, the film by Corry, Wurlitzer and Hellman (let’s give each one credit for what’s theirs) rewrites an entire widespread mythology with systematic modifications. In other words, it takes key themes from a fundamentally American art and puts them in a new figurative wrapping. The cars undoubtedly represent the horses of western films, and the car race alludes to the duels that were so central to many such movies. We could even go as far as to say that the roles of the ‘young’ and the ‘old’ are represented in a reversal that bestows wisdom upon the first and turns the second into mere tellers of stories from which nothing can be learnt. The linguistic precision of the conversations between The Driver and The Mechanic, which only concern their work and the technical problems of their mechanical steed, contrast with the multiple autobiographical tales that GTO uses to dazzle the hitchhikers he picks up along his journey, and which are nothing but empty chatter. In the first case, we know nothing about their lives beyond what goes on their professional practice (driving, maintenance)[7], and in the second what we have is a character split between several tales, each more fantastical than the last. It’s no coincidence that the confrontation takes place between a hot rod (by definition unique) and an as-standard car. Singular creativity is thus pitted against the commercial stereotype that tries to provide a rigged version of an original experience. In other words, not only are the cars themselves main characters but rather they can be seen as a symbol of two opposing ways of understanding film, one of which is represented by the move that we are discussing here.

Without a doubt, the film’s most significant gesture is the return to the idea of the journey westward; a trip which is so transcendental in the culture and formation of the American nation. It invites us on a journey home. At the end of the road, all that’s left is to return, though where to is unclear. All that exists is the journey itself. It is the only place to which one can belong. Moreover, the film aesthetic does a good job of showing that the journey takes place along the mythical Route 66, which crosses the country from east to west along the eponymous two-lane roads that give the film its title and gives us a front-row view into the American ‘backyard’. For example, various scenes take place in the nocturnal world of clandestine races, and the main characters steal registration plates so that they can safely drive through redneck territory.

Hence, this wrong-way-round journey is expanded as there are more and more coincidental encounters with various small catastrophes (a road accident; GTO’s encounter with an old woman and a girl on their way to the cemetery where the girls’ parents now lie after being killed in a road accident a few days prior). When it comes to the famous final scene, we move from the level of the narrated story to that of the cinematographic techniques used to set the scene for the end of the tale. The resolution of the story is left in suspense, and one more step in the very nature of cinematography is revealed. Let’s turn to Monte Hellman's own words: ‘The script ended with GTO driving off into the sunset. I asked Rudy [Wurlitzer] to write a coda showing the road with the townsfolk that The Driver challenges outside a coffee shop in North Carolina. And I asked him to end the movie with the film coming to a halt and burning in the projector.’ As fervent admirer of the film Richard Linklater has said, this is the most purely cinematographic ending in the history of the seventh art. Either way, it’s impossible not to think that the director was revealing his awareness that the end of his film was also the end of an opportunity that would perhaps never present itself again.

[1] This process would culminate in the 1980s with Coca-Cola’s purchase of Columbia in 1982, the acquisition by a thriving cable TV company (Turner) of MGM in 1985, and the Murdoch’s takeover of 20th Century Fox that same year. But that's another story.

[2] Hot rod was slang for a car that was modified for increased speed. The practice started out in the 1920s and become popular in the 1950s in the San Fernando Valley area to the north of Los Angeles, which was the scene for a series of clandestine night races and the exchange of significant sums of money in bets.

[3] The credits cite Will Corry as the story writer and co-writer of the screenplay together with Rudy Wurlitzer.

[4] Also musical mentor to one Charles Manson.

[5] This scene also highlights another of Hellman's methods: stick for the most part to the dialogues in the script while encouraging the 'actors’ to make the character their own and change it if they feel the need. In this case, the ambient sound is also integrated into the dialogues to shape the ‘here and now’ of the shoot.

[6] In the 1970s, Gary Kurtz would become one of George Lucas's key collaborators, producing American Graffiti (1973), Star Wars (1977) and The Empire Strikes Back (1980).

[7] Wurlitzer's script describes the character of The Driver as follows: ‘When he drives he becomes one with The Car. When he’s out of The Car he seems slightly lost, as though he's lost his own centre’.

[A1]Errata en el texto fuente.

[A2]Errata en el texto fuente.

[A4]Errata en el texto fuente.

[A5]Errata en el texto fuente.

Presented by Santos Zunzunegui.