Twelve-part series that explores the changing production model by which the old Tabacalera factory became the current International Cultural Centre. Lurking two big questions: what do we need from the past when it comes to work? and how and from where one can speak of memory ?.

Tabakalera embodies these and many other issues, which has allocated a small space in the building, Storage, where the series is shown as a video installation, adding a chapter each mid-month, starting from the inauguration on September 11, until September 2016. The project by Cruza Marte, is accompanied by a public side events.

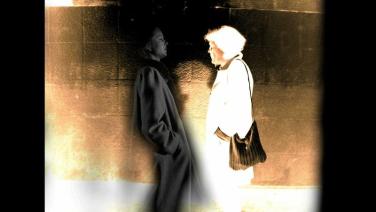

Chapter 5 (22' 52'') - Operation Carmen

Concerning the reason given by the citizens of the Swiss town Appenzell in order to ban women suffrage (that is «they already gave their vote by counselling their husbands»), Maria Lafont, always careful and to the point, said that:

«The village whose chairs one can only occupy by sentimental suffrage is a clumsy one».

She states it in her work Essay Against Feelings. It is a brief and pleasant book; you read it as fast as dogs become hungry again. It is divided in little scenes. I am especially curious about the scene on Carmen, the cigar maker, Mérimée's and also Bizet's character.

«Even though, in Carmen, the coexistence of fascination and fright is as uncomfortable as the handshaking between my left hand and my right one, it is impossible for me to find in her any sort of fantasy about a paradise lost (a paradise of beauty, freedom, utopia). Bizet was not a revolutionary at all. His composition navigates a sea of tendencies with an antique vessel. He makes use of the flow of tragedy, but it is sheer exaltation. In my view, it belongs to the sentimental outpouring genre».

I read that just before my twenty-minute nap. I always read something. Usually, I take advantage of the moment when reading brings me some thought, and then I close my eyes and slide, slowly and entertained, into rest. Well, today, it is impossible for me to sleep calmly, for, time after time, the characteristic little altered images of light sleep come to me, an intuition that seems an idea resists evaporation in midst of the drowsiness of sleep and given that I am a stubborn woman who draws special attention to lost causes, how can I possibly cease to protect this small and new-born idea which oneiric avalanche is about to engulf? I then listen to Maria Callas, singing the aria «Love is a rebellious bird», the well-known habanera in Carmen. According to the song, the aforementioned bird, flies all over, and when you think you got it, it escapes you, and when you think you have escape it, it gets you. No doubt, this is the infant Cupid, who is transformed into a graceful bird, so that the painteresque becomes even more lustful. Nevertheless, as a friend who is clumsy but at the same time an expert on operas and operettas told me, for he knows the sweet beauties of these works, the little bird is also Carmen's sex, which opens up at flying, which becomes public, ready to be hunt, offering itself to the phallic machine gun that will aim at it accurately («the same happens, in another way, to the flower Carmen gives Don José, and, generally, to all the flowers and birds that appear in beautiful landscapes just around nice girls»). However, in this light sleep, Carmen is not only a copy of masculine cowardice (and in the end, it is the same old cowardice, right?), but also the gypsy, the thief, the smuggler, the bandit, the terrorist, the one who does her thing, the traitor, the despicable, the tasteless. Carmen is all of that and much more; even more, the character that Mérimée put into the trigger of culture has become, little by little, a mule of symbolic load.

I woke up fatigued. I must admit that Carmen is not my dearest opera. It is more of a long company than an opera, an insistent repetition, interrupted by logic variations. It is not unlike christmas. I find it more similar to the orchestral covers and kitsch flamenco songs played in open-air dances, stalls, skating rinks and summer galas, than the sort of music that I would pleasantly listen to in the light of a calm afternoon. Carmen is a museum... a wax museum. I ask myself about the character's future, cut short. The character has died many times, a thousand times, killed by Don José. There is no old age for Carmen, she was denied of it; such a sentence. Is not she in a way incarcerated, isolated, disenfranchised in an exile of uselessness? I am intrigued by this impossibility of an old Carmen. I want her existence, even if unfortunate. I want her glance, her attention, beyond the seas of her past life. I want her presence, vouching for the present. I want her freedom, and not the full stop where she has been shut away. This is the Carmen whose music I would listen to with pleasure, the Carmen from whose lips I would await the verses of a good conversation («we women should talk», she would say), the Carmen whose gestures, seated on top of her good choices and errors, would show me the dusk lights, those lights which bathe with calm happiness our common longings.