From the ‘visual ray’ metaphor to Pierre Jules César Janssen’s ‘revolver photographique’, the history of optics and the history of ballistics developed in parallel to one another, ultimately conflating in the figure of the drone: a camera that can kill.

Curatorial Statement

In 1768, England’s Royal Academy sponsored an expedition to Tahiti, whose mission was to construct an astronomical observatory, in order to observe Venus gliding across the face of the Sun. This was the ‘Transit of Venus’, an elusive astronomical phenomenon that occurs only twice every century. Lt. James Cook was in command, on a ship named the HMS Endeavour. The trip was, however, a land grab disguised as scientific expedition: Cook carried secret instructions to scour the South Pacific, searching for a continent, the Terra Australis Incognita, an unknown ‘south land’ mass, which turned out not to exist. Instead, he claimed the whole of the east coast of Australia for Great Britain on 22 August 1770, naming eastern Australia ‘New South Wales’. Regarding the transit of Venus, the expedition was less successful.

The first device capable of recording a series of sequential photographs was developed by an astronomer, Pierre Jules César Janssen, in order to observe the 1874 Transit of Venus. The ‘revolver photographique’ was a huge camera system equipped with a cross-shaped mechanism, similar to the disk in a colt revolver, able to rotate clockwise, taking 48 exposures in 72 seconds on a daguerreotype disk. Unlike Eadweard Muybridge’s earlier experiments, the ‘revolver’ did not require a series of separate cameras. Janssen’s apparatus led to the invention of chronophotography, when in 1882 Étienne-Jules Marey adapted and improved it into a device capable of capturing 12 frames per second. Though chronophotography’s original purpose was to help scientists study objects in motion, the new field swiftly developed into a broader industry. As astronomy moved away from the field of optics altogether, embracing the higher accuracy yielded by physics, chronophotography ceased to be an obscure technology used for astronomical measurements or studies of motion, and became instead the defining medium of modernity – the most powerful manifestation of the budding entertainment industry.

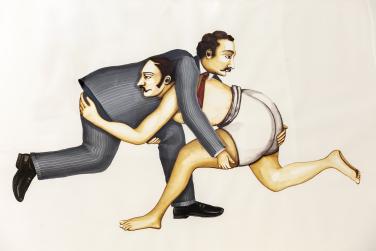

From the ‘visual ray’ metaphor to Pierre Jules César Janssen’s ‘revolver photographique’, the history of optics and the history of ballistics developed in parallel to one another, ultimately conflating in the figure of the drone: a camera that can kill. But under the aegis of, and working in tandem with, this technoscientific trajectory one finds a whole racialised and gendered regime of visibility, suggesting an ideological process at work ‘making what is contingent and local, perhaps even idiosyncratic, in matters of taste appear to be natural, and thus beyond dispute’1. The present exhibition aims to map the structuring force of this white gaze in its concrete and abstract dimensions, thematising – among other threads – the entanglements of aerial perspective with total war and the creation of death-worlds; questions of transparency and opacity; and what cultural theorist Jonathan Crary termed ‘the inversion of the gaze’, when the screen doubles as a surveillance device that watches the viewer watching it.

1 Meg Armstrong, "The Effects of Blackness": Gender, Race, and the Sublime in the Aesthetic Theories of Burke and Kant, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 54. bol., 3. zk. (1996): 213–236. or.

Curators: Ana Teixeira Pinto and Oier Etxeberria Bereziartua, in collaboration with Germán Labrador.